Twenty Years Ago Today

I’ve been avoiding writing this for twenty years. And every time I think about it and then don’t write it, I feel a little more guilty, because I know the information I have might help other women, other families, other babies. Now especially.

But I don’t write it, because just thinking about it—something I try to do every year at this time—takes me back there. Puts me back inside a nightmare that never really goes away. It’s not that it consumes me anymore, it doesn’t. The rest of my life has grown up around it, and given me space to be happy again. But it’s never gone away. Just thinking about it, or opening up that box, takes me right back there.

Right back to that hard table, in that thin hospital gown, looking up every few minutes at the big round clock on the wall. The image on the screen, the doctors’ words…

That sudden plunge, from the exhilaration of expecting a new baby, to this… is too much for a human being to handle. A part of my brain knew that. And I remember so clearly what it did to protect the rest of me. As the doctor was explaining to us that our son was “no longer living,” I experienced something happening inside of me. It was as if some executive function had stepped up and said to the rest of me “no, you don’t get this information yet. It’s too much for you. Not now.” And then that executive function, that part of my brain, whatever it is, pulled a lever that brought a wall down between itself and the rest of me. The parts that couldn’t yet handle what they were being told.

I think people call it “going into shock.” But it didn’t feel like shock. It felt cold and empty and numb.

Afterwards, I sat up on that same table, my arms outstretched for the nurse to take a blood sample.

“Just take it all,” I was thinking. “Take all of it.”

I do try to go back every year. I don’t always succeed.

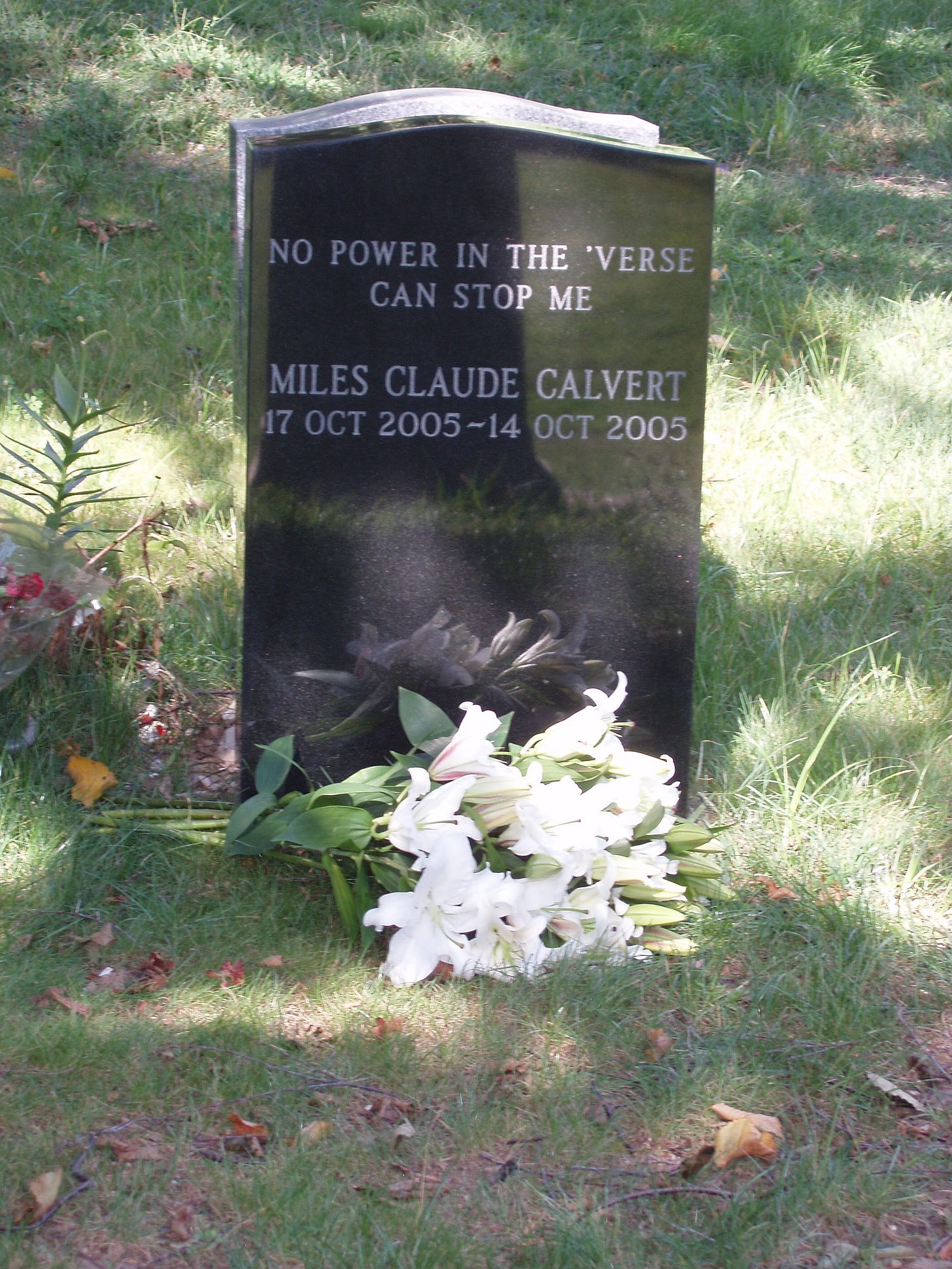

Our baby, Miles, was 39 weeks old when he died from a cord accident in the womb, twenty years ago today. We later learned that my risk of stillbirth at that time—that is, the rate of full-term babies who die in the womb—was around one out of a hundred and fifteen. That number astonished me. I had thought that stillbirth was something that only happened in Victorian novels.

My risk, at that time, of having a baby with Downs Syndrome, was only slightly higher: about one in a hundred. Yet our OB/Gyn had strongly encouraged us to see a genetics counselor, and to have an amniocentesis done—even after I told her that the outcome wouldn’t make a difference because I would not abort a baby with Downs.

She actually tried to talk me out of my position, even saying—when I told her that most of the people I’d known with Downs Syndrome seemed pretty happy—that we “don’t know” if those with Downs are happy or have good lives. (It only later occurred to me that I wasn’t entirely sure if she was happy or had a good life.)

That should have been my first red flag.

That doctor never told us that my chances of having my baby die at 20 weeks or later were nearly as high as the chances of his having Downs. It was a stark and ugly lesson for me in where the priorities of the OB/Gyn profession lay.

Having spoken with more OB/Gyn doctors, and heard about others’ experiences, I now believe that the profession is dominated by eugenicists. My advice to new mothers: Find an OB/Gyn who is openly Christian. Even if you are not Christian yourself. You won’t regret it.

My other piece of advice: Learn about the work of Doctor Jason Collins, and plan to closely monitor your baby in the final months of pregnancy.

After we lost Miles, we learned about Dr. Collins’ work studying the causes of stillbirth and developing a protocol to prevent it. According to Dr. Collins’ research, a large percentage of stillbirth deaths are the result of some kind of problem with the cord: Either the cord wrapping around the baby’s neck, getting tied in a knot, becoming badly kinked, or getting under some other kind of pressure that impedes blood flow.

What Dr. Collins also found is that these problems can often be detected through extended monitoring. We worked with Dr. Collins for both of my later pregnancies to monitor for heart rate patterns that might indicate a problem, and were prepared to take action if there was one.

Now of course, in 2025, the kind of cord accident that killed our baby is not the only—nor, probably, even the most common—cause of stillbirth. Since the release in late 2020 of the Covid-19 mRNA “vaccines”, both stillbirths and miscarriages have skyrocketed among women who received these products.

Some surveillance data shows a 90% risk of miscarriage or stillbirth for women vaccinated during the first or second trimesters of their pregnancy both in the US and in the UK. And Naomi Wolf’s WarRoom/DailyClout team’s examination of Pfizer’s own data found that “… about 270 women got pregnant during the study. More than 230 of them were lost somehow to history. But of the 36 pregnant women whose outcomes were followed - 28 lost their babies.

Twenty years after losing Miles, I can honestly say that I no longer experience a powerful twinge of emotion—rage, mixed with envy, fear and I guess maybe even some empathy—whenever I see a pregnant woman. I no longer feel the need to run up to her and try to wipe the innocent smile off of her face, to yell at her that she has no idea how dangerous things are, how terribly badly things could still go.

I never did run up to pregnant women and say these things, of course, but perhaps I should have. Because their doctors sure won’t.

I don’t blame my doctor for our baby’s death. I don’t even blame the medical establishment and its “standards of care.” But it sure would have been nice to have known how high the risk of stillbirth was, and it would have been even nicer to have known about the work of Dr. Collins, to have some way of minimizing that risk.

We buried our son about a week after he died, in a beautiful cemetery in Brooklyn. As we held our ceremony, one of the men who had dug his grave, having seen the size of the coffin, stood and wept.

When I left a message with my doctor’s answering service, the operator who took the message started to cry on the phone.

When our baby’s aunt stopped screaming, she said “I hope he knows how much we loved him.”

It was many weeks before I felt able to go out in public again. I thought at the time that it was a big mistake for us to have given up on visible signs of mourning. We’ve lost (or thrown away) something important: Seeing your loss in the faces of other people helps to make it tangible, helps to confirm that it mattered. That your baby mattered.

When you suffer a loss like this, it shatters you, and even when you’re ready to venture out into the world again, it is as a weak shadow of your former self. All of time stands still now, and it is incomprehensible to you that others are still getting on with their lives, still rushing to meetings, talking about work, or food, or movies… as if any of that matters. Don’t they know?

With stillbirths and miscarriages rising to unbelievable levels in the past few years, I wonder how many of these flimsy shadows are walking among us now. The thought haunts me. We no longer wear veils, or even arm bands, to alert the world to our grief. If we did, I wonder what the world would look like now. I wonder if the rest of us could stand to see it.

Bretigne, it's hard for me to adequately express to you in words after reading this heartbreaking post: Just know that you and your family are loved. ALL of you. Big hugs. And thank you for sharing.

Someday, if and when you're ready, I can share a personal story with you privately...

Thank you for sharing such a deeply personal story. I’m sure he would have been a great guy. I trust in God for a better place and one golden day I hope to see loved ones who love the Lord again. God bless. 😢🙏🏻